Asynchrony in Python - Event loop | Part 2

March 29, 2021One of the important concepts in programming is the event loop or event loop. It's not an exaggeration to say that event loops are the heart of asynchronous programming in languages like Python or Javascript, ...

This is my next article in a series of articles on asynchronous programming in Python. You can follow your previous article about coroutine before reading this article. Let's get started now Let's go

An event loop (or event loop) is a loop (unlimited or finite), which browses through all tasks and executes them. Event loops also have the role of maintaining these tasks in a queue. After you create a task, it will be pushed into this queue by the event loop to be scheduled and executed.

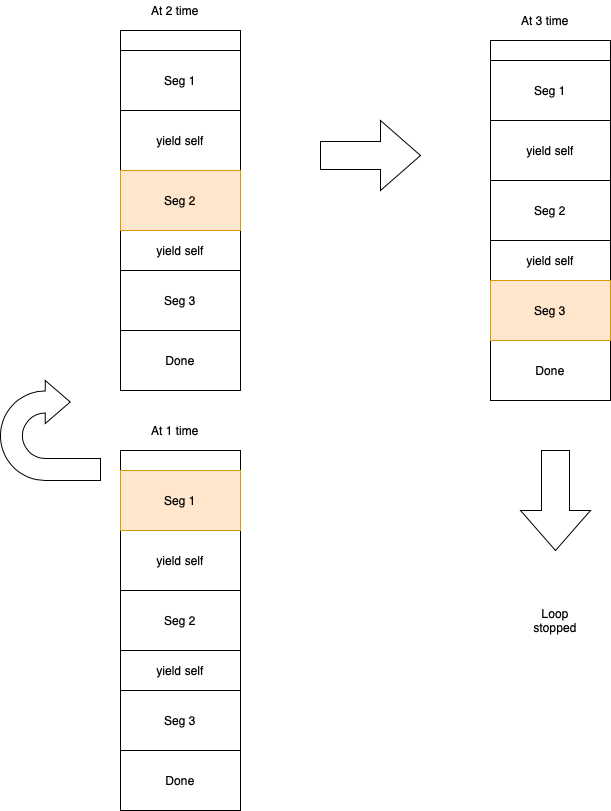

The picture below shows us the basic view of how an event loop works. It's very simple to understand, isn't it.

Event loop

Recalling in the previous article, I said that coroutines can remember the location where it returns program control for that coroutine call and it can restart at that location on the next call.

Một hàng đợi sẽ chứa (maintain) các coroutine và với mỗi coroutine sẽ được thực thi đoạn code nằm giữa 2 lời gọi yield (đây chính là trap trong OS) bởi vòng lặp sự kiện.

The state of the coroutines will be saved in the static memory space of that coroutine itself and then the coroutine will be pushed into the queue (wait for the next turn if it is not finished).

The event loop will stop only when this queue is empty or it is terminated halfway, which will depend on the programmer as well as the policy of the specific event loop type.

Here you can ask what is the policy of the event loop? For simplicity, I will explain this concept in the next article.

How can event loops execute and maintain tasks?

Event loop with a task (coroutine)

After the task is partially executed (not finished), it will return control to the caller (event loop) after changing and saving its internal state. At this point, the event loop already has control over the program and will push the task into the queue.

Okay, now let's try writing an asynchronous program using a generator (a simple form of coroutine).

To cater to these complex requirements, we will wrap coroutine in a class as follows:

class Task:

def __init__(self, waiter=None):

self._task = iter(self)

self._waiter = waiter

def __iter__(self):

yield self

def execute(self):

try:

ret = next(self._task)

except StopIteration:

return self._waiter

else:

return ret

You can see that every time we call execute_task, the coroutine is executed (ret = next(self._task)).

If the task is truly finished, it will tell the event loop, "I have completed execution, please schedule the waiting ones" (return self._waiter).

If the task is not yet finished (waiting for results from a socket, for example), it will say, "I'm not done yet, I still have to wait for data. Please schedule me to execute later."

Okay, the task will only do such simple things. 😄

Now, let's define an EventLoop class that should be simple enough for us to understand easily.

import queue

class EventLoop:

def __init__(self):

self._queue = queue.Queue()

def push_task(self, *tasks):

for task in tasks:

self._queue.put(task)

def _run_by(self, stop_fn):

_queue = self._queue

while not stop_fn():

task = _queue.get()

next_task = task.execute()

if next_task:

self.push_task(next_task)

def run_until_complete(self):

self._run_by(self._queue.empty)

def run_forever(self):

self._run_by(lambda: False)

The purpose of the EventLoop is also extremely simple.

The push_task function is a scheduling function, and simply pushes the task to be scheduled into the queue.

_run_by is also quite understandable. It retrieves tasks from the queue and executes them. If there are tasks that need scheduling, it schedules them until it encounters a stopping condition (stop_fn) to stop or, in Python terms, it would be closed.

After the preparations are done, we can write a simple asynchronous program as follows.

import time

current_loop = None

class Sleep(Task):

def __init__(self, *args, n=0, **kwargs):

super().__init__(*args, **kwargs)

self._n = n

self._start = time.time()

def __iter__(self):

while 1:

if time.time() - self._start > self._n:

return self._waiter

yield self

class Ping(Task):

def __iter__(self):

print('Start ping')

yield Sleep(self, n=3)

print('End ping')

class Pong(Task):

def __iter__(self):

print('Start pong')

yield Sleep(self, n=2)

print('End pong')

current_loop = EventLoop()

current_loop.push_task(Ping(), Pong())

current_loop.run_until_complete()

You can see that the above code snippet is equivalent to the following async/await code: 😄

import asyncio

def ping():

print('Start ping')

await asyncio.sleep(3)

print('End ping')

def pong():

print('Start pong')

await asyncio.sleep(2)

print('End pong')

task = asyncio.gather(ping(), pong())

asyncio.run(task)

Then result

Start ping

Start pong

End pong

End ping

A small exercise with significant impact:

Please compare await and yield.

- In the async/await code snippet, which part is the waiter?

- If you can answer these two questions, it means you have a good understanding of the event loop and the essence of the async/await keywords.