Asynchrony in Python - Coroutine | Part 1

March 19, 2021Asynchrony is a very common concept in programming languages such as Javascript, Kotlin or Python. In particular, programmers who work as much with networking as web developers often have to work with this concept. In this article, I will explain one of the components that make up the async programming ecosystem in Python and of course, it also brings this idea to some other languages.

Goal

- Learn and compare programming models for asynchronous handling problems

- Asynchrony and some approaches

- What is Coroutine? How do they work? Compare processing units

- Coroutine in practical application

What is asynchrony?

According to Wikipedia

Asynchrony, in computer programming, refers to the occurrence of events independent of the main program flow and ways to deal with such events. These may be "outside" events such as the arrival of signals, or actions instigated by a program that takes place concurrently with program execution, without the program blocking to wait for results. Asynchronous input/output is an example of the latter cause of asynchrony, and lets programs issue commands to storage or network devices that service these requests while the processor continues executing the program. Doing so provides a degree of parallelism

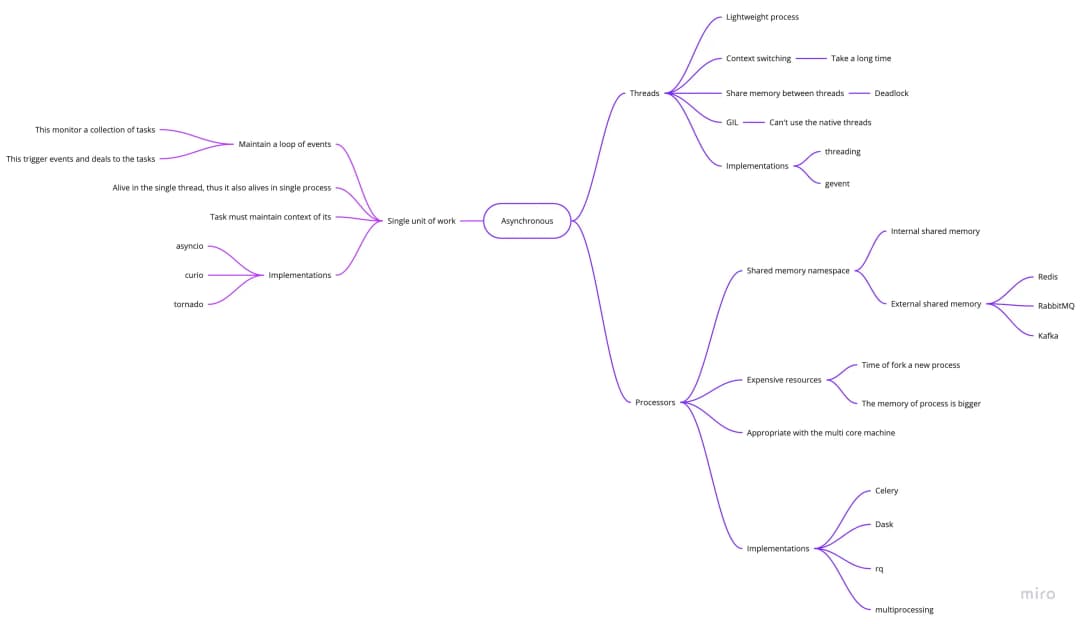

The image below shows us some solutions to asynchronous problems

Note, threads in Python are native threads, but due to some policies (specifically in cpython), GIL (Global Interpreter Lock) will not allow them to run 2 threads simultaneously. Therefore, Python threads do not handle them in parallel and I really don't like using them because:

- Waste of maintenance resources

- Fork a new thread is extremely time consuming

We can see that threads and processes both have their own memory space, so they can perform tasks independent of the main thread or main process.

On the contrary, event loop maintains tasks, these tasks share common memory and we must answer the question: How we can organize the memory space for isolated tasks?

When do we use event loop, thread or process?

In computer science, we can divide tasks into 2 types:

- CPU bounded

In computer science, computers are bound by CPUs (or computer limits) when the time it takes for it to complete a task is mainly determined by the speed of the central processor: high processor usage, which can be at 100% usage for seconds or minutes. Interrupts generated by peripherals can be handled slowly or delayed indefinitely.

- I/O bounded

I/O constraint refers to the condition in which the time it takes to complete a calculation is primarily determined by the time it takes for in/out operations to be completed. This is the opposite of a task bound by the CPU. This case arises when the data rate is taken slower than the rate it is used or, in other words, spend more time taking the data than processing it.

Example:

- using multiprocess (native thread) for I/O bound

Jason asked David 'What are you doing today?' and David replied that his jobs are waiting to be tested and he has no tasks at all so he will go home and 😴

No, it is not an optimal solution. Instead, David should do other tasks until Ms.Tee says 'Hey David, your tasks have not been achieved, fix it' 😥

Exactly this is how event loop works for tasks bound by I/O

- use event loop for tasks bound by CPU

Your group has 5 members and 5 tasks but only David does all those tasks. Because each task has to be committed at the end of each day, David does one task for 1 hour and moves on to another task. Therefore, on weekends, he was exhausted and sick 😷

No, we have 5 members, why are we pushing all the work for David? Jason can assign tasks to other members and at the end of each day, tasks are still committed and David is fine.

This is how multi-process processing does it.

Through the above example, we find that event loop is only really useful in problems related to IO bound. They are used in event systems and similar systems. They may be the best solution to problems related to IO bound.

Problems in event loop model

We already know that we have a context of any function. This context consists of variables and they are released after the function ends (released from the stack).

In the I/O-bound task, we will have some data commands (IO operation) where we need to optimize (such as David, for example, he can suspend tasks pending by test and switch to another task and then return to his tasks).

So interrupts are a problem, how can we create interrupts in the function while keeping the context of the function so that we can continue to execute?

At those interrupts, the executable function (callee) needs to give program control to the place where the function was called (caller), here it is actually an event loop and we also need to start at this breakpoint when the caller gives control to callee when it is executed again.

The solution here is to use coroutine

What is the coroutine?

Donald Knuth said:

Subroutines are a basic case of coroutine

Exactly, generalization, the normal functions we often use (the function that releases context after exiting the function) is a special case of coroutine - where context can be retained when it is temporarily used.

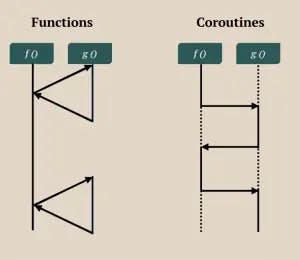

Subroutine vs Coroutine

Why is coroutine useful for event system?

- is non-preemptive scheduling

- can pause and resume anywhere so if data is stream, they can save memory

- can maintain the state

- with I/O constraints, memory and CPU optimization coroutine

- they are compact

Unit of work

| Process | Native thread | Green thread | Goroutine | Coroutine | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bộ nhớ | ≤ 8Mb | ≤ Nx2Mb | ≥ 64Kb | ≥ 8Kb | ≥ 0Mb |

| Quản lí bởi OS | Yes | Yes | No | No | No |

| Không gian địa chỉ riêng | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| Pre-emptive scheduling | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Khả năng song song | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No |

The question is: So how does coroutine work?

How to install a coroutine?

#include <stdio.h>

int coroutine() {

static int i = 0, s = 0;

switch (s) {

case 0:

for (i = 0;; ++i) {

if (!s) s = 1;

return i;

case 1:;

}

}

}

int main(int argc, char** argv) {

printf("%d\n", coroutine()); // ?

printf("%d\n", coroutine()); // ?

printf("%d\n", coroutine()); // ?

return 0;

}

Basically, it attempts to preserve the state of the function in variables i and s acting as a checkpoint. Before suspending the function, the variable s is set as the starting point when it is resumed.

In this code snippet, the main point is the variable s and how the code can resume and suspend the coroutine by using a switch case.

And below, it is converted to Python code from C code above

def coroutine():

i = 0

while 1:

yield i

i += 1

co = coroutine()

next(co)

next(co)

next(co)

Can you convert this Python code to C?

def fib():

a, b = 0, 1

while True:

yield a

a, b = a + b, a

co = fib()

for _ in range(10):

print(next(co), end=' ')

Then you should see like this

0 1 1 2 3 5 8 13 21 34

I can build any coroutine in C. Can you do that?

#include <stdio.h>

int fib() {

static int i, __resume__ = 0;

static a = 0, b = 1, c;

switch (__resume__) {

case 0:

for (i = 0;; ++i) {

if (!__resume__) __resume__ = 1;

c = a + b;

b = a;

a = c;

return a;

case 1:;

}

}

}

int main() {

for (int i = 0; i < 10; ++i) {

printf("%d ", fib());

}

return 0;

}

def say():

yield "C"

yield "Java"

yield "Python"

co = say()

print(next(co))

print(next(co))

print(next(co))

print(next(co))

The results can be seen

C

Java

Python

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

StopIteration Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-1-913b1d7d4200> in <module>

8 print(next(co))

9 print(next(co))

---> 10 print(next(co))

StopIteration:

#include <stdio.h>

char* say() {

static int __resume__ = 0;

switch (__resume__) {

case 0:

__resume__ = 1;

return "C";

case 1:

__resume__ = 2;

return "Java";

case 2:

__resume__ = 3;

return "Python";

default:

return NULL; // GeneratorExit

}

}

int main() {

printf("%s\n", say());

printf("%s\n", say());

printf("%s\n", say());

printf("%s\n", say());

return 0;

}

We can see that coroutine needs a static memory space to save the state when it suspends and restores without losing the context. In C, static spaces are static variables, which are maintained by the OS when a function exits. In Python, the context of the function is stored in stack frames.

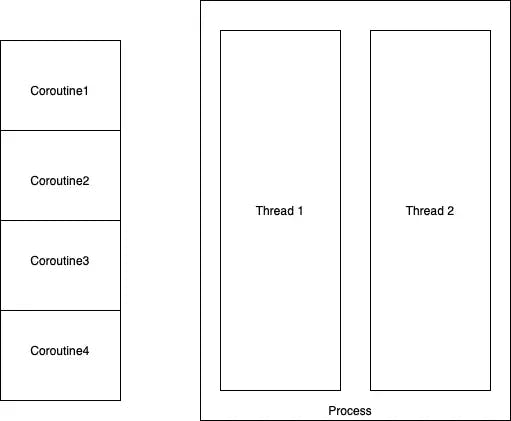

Think of coroutines as fragments of a program, have no separate memory, no parallel execution, and are extremely secure.

Coroutine vs Thread

Coroutine reduces errors caused by multi-process (multi-threaded) processing and I think it is the best solution for networking-related tasks because it only exists in 1 process.

In Python, we can define coroutines by using the "yield" statement within function definitions. When we call the function, it returns a coroutine instead of a final result.

def coro_fn():

val = yield 'Starting' # started coroutine and suspend, return control to caller

print('Consume', val)

yield 'Hello World' # produce data

co = coro_fn() # create a new coroutine object

print(co.send(None)) # start coroutine

print(co.send('data')) # resume coroutine, pass control into coroutine

co.close() # close coroutine

Then the results can be seen

Starting

Consume data

Hello World

Generators are a special case of coroutine, they can only generate data without being able to consume (consuming) data.

def g1():

for i in range(10):

yield i

def g2():

for i in range(10, 20):

yield i

def g():

for i in g1():

yield i

for i in g2():

yield i

list(g())

And here is the result

[0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19]

We can refactor the code with yield from

def g():

yield from g1()

yield from g2()

list(g())

Build binary tree with yield from

class Node:

def __init__(self, value=None, left_nodes=None, right_node=None):

self.left_nodes = left_nodes or []

self.right_nodes = right_node or []

self.value = value

def visit(self):

for node in self.left_nodes:

yield from node.visit()

yield self.value

for node in self.right_nodes:

yield from node.visit()

root = Node(

0,

[Node(1, [Node(7), Node(8)]), Node(2, None, [Node(9), Node(10)]), Node(3)],

[Node(4), Node(5), Node(6)]

)

for value in root.visit():

print(value, end=' ')

7 8 1 2 9 10 3 0 4 5 6

Application of coroutine

1. Asynchronous TCP server

In this case, a TCP server is an event system

- Event source: listening socket and connection sockets

- Basically, we have two types of events: EVENT_READ, EVENT_WRITE and the tasks are coroutines, each task will handle 1 event of 1 connection at a time

- We also have an event loop, it is an I/O multiplexing for file descriptor

import logging

from sys import stdout

from socket import socket, SOCK_STREAM, AF_INET

from selectors import DefaultSelector, EVENT_READ, EVENT_WRITE

logging.basicConfig(stream=stdout, level=logging.DEBUG)

class Server:

def __init__(self, host, port, buf_size=64):

self.addr = (host, port)

self.poll = DefaultSelector()

self.m = {}

self.buf_size = buf_size

def handle_read(self, sock): # tạo ra một context độc lâp cho mỗi kết nối

buffer_size = self.buf_size

handle_write = self.handle_write

def _can_read():

chunks = []

while 1:

chunk = sock.recv(buffer_size)

if chunk.endswith(b'\n\n'):

chunks.append(chunk[:-2])

break

else:

chunks.append(chunk)

yield

handle_write(sock, b''.join(chunks))

handler = _can_read()

self.m[sock] = handler

self.poll.register(sock, EVENT_READ, handler)

def handle_write(self, sock, data): # tạo ra một context độc lâp cho mỗi kết nối

poll = self.poll

m = self.m

buffer_size = self.buf_size

def _can_write():

nonlocal data, sock

start_, end_ = 0, 0

data = b'Hello ' + data

len_data = len(data)

while 1:

end_ = min(start_ + buffer_size, len_data)

if start_ >= end_:

break

sock.send(data[start_:end_])

start_ += buffer_size

yield # trả quyền điều khiển cho event loop để chờ đến khi socket sẵn sàng ghi

# đóng và giải phóng các socket

poll.unregister(sock)

del m[sock]

sock.close()

del sock

handler = _can_write()

m[sock] = handler

poll.modify(sock, EVENT_WRITE, handler)

def handle_accept(self, sock):

while 1:

s, addr = sock.accept()

logging.debug(f'Accept the connection from {addr}')

self.handle_read(s)

yield

def mainloop(self):

try:

sock = socket(AF_INET, SOCK_STREAM)

sock.bind(self.addr)

sock.setblocking(0)

sock.listen(1024)

self.m[sock] = self.handle_accept(sock)

self.poll.register(sock, EVENT_READ, self.m[sock])

logging.info(f'Server is running at {self.addr}')

while 1:

events = self.poll.select()

for event, _ in events:

try:

cb = event.data

next(cb)

except StopIteration:

pass

except Exception as e:

sock.close()

self.poll.close()

raise e

Bạn có thể chạy nó

server = Server('127.0.0.1', 5000)

server.mainloop()

Scheduler and task in actual libraries: Kernal curio

2. Streaming system

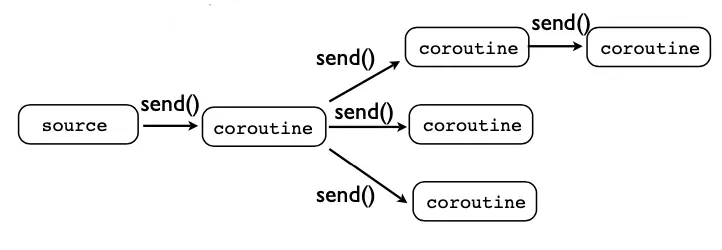

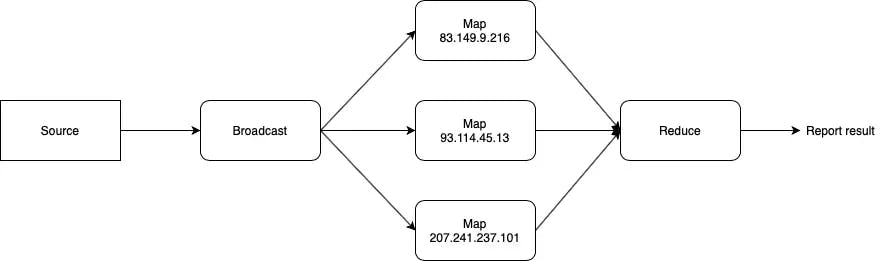

We can use coroutine to build a data processing system. Basically, the system separates small blocks of logic. They are placed in coroutines with their own context. You can see them in the image below.

Mô hình xử lí dữ liệu

Event source can be Redis pub/sub, Kafka, RabbitMQ or user interactions,...

We can describe any type of system if we create we have a specific logic block: data filter block, condition block, selector, broadcast block...

For example: build a webserver's access IP address analyzer

First, you need a log data file

Thống kê IP

def coroutine(f):

def decorator(*args, **kwargs):

co = f(*args, **kwargs)

co.send(None) # start coroutine before it's used

return co

return decorator

@coroutine

def broadcast(targets):

try:

while 1:

data = yield

for target in targets:

target.send(data)

except GeneratorExit:

for target in targets:

target.close()

@coroutine

def map_(ip, next_):

try:

while 1:

data = yield

if data.startswith(ip):

next_.send(ip)

except GeneratorExit:

next_.close()

@coroutine

def reduce_(on_done):

m = {}

try:

while 1:

data = yield

if data not in m:

m[data] = 1

else:

m[data] += 1

except GeneratorExit:

on_done(m)

Sau đó chạy

result = {}

def on_done(r):

global result

result = r

reducer = reduce_(on_done)

flow = broadcast([

map_('83.149.9.216', reducer),

map_('93.114.45.13', reducer),

map_('207.241.237.101', reducer),

])

# this is the source data

# We have 10000 lines in this log

%time

with open('assets/files/access.log', 'r') as fp:

for line in fp.readlines():

flow.send(line)

flow.close()

print(result)

The results can be seen

CPU times: user 2 µs, sys: 1e+03 ns, total: 3 µs

Wall time: 5.25 µs

{'83.149.9.216': 23, '93.114.45.13': 6, '207.241.237.101': 17}

Improvement

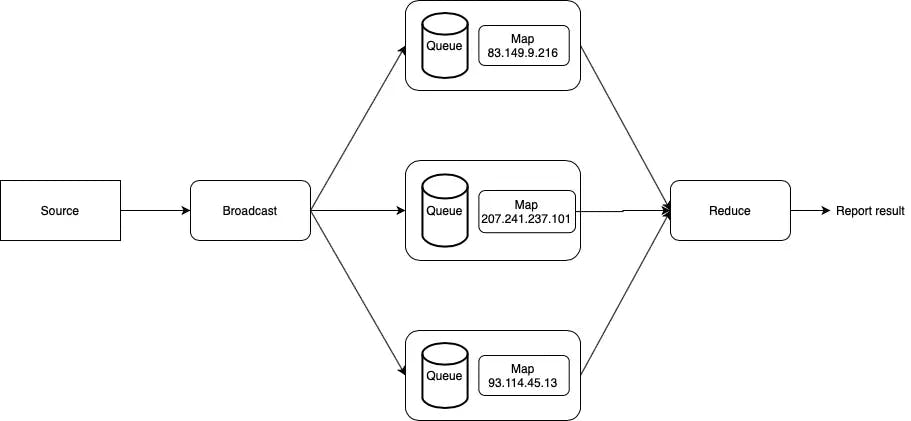

We can wrap threads in a couroutine, why not?

Simply, we use threads instead of machines

OK let's design at the diagram

Kết hợp coroutine và thread

In the diagram above, I moved logic into threads and used queues as communication channels with threads.

Not only that, rows also act as buffers if the input speed is greater than the output speed of that processing unit.

from threading import Thread

from queue import Queue

def coroutine(f):

def decorator(*args, **kwargs):

co = f(*args, **kwargs)

co.send(None)

return co

return decorator

@coroutine

def broadcast_threaded(targets):

queue = Queue()

def _run_target():

nonlocal queue, targets

while 1:

data = queue.get()

if data is GeneratorExit:

for target in targets:

target.close()

return

else:

for target in targets:

target.send(data)

Thread(target=_run_target).start()

try:

while 1:

data = yield

queue.put(data)

except GeneratorExit:

queue.put(GeneratorExit)

@coroutine

def map_threaded(ip, next_):

queue = Queue()

def _run_target():

nonlocal ip, queue

while 1:

data = queue.get()

if data is GeneratorExit:

next_.close()

return

else:

if data.startswith(ip):

while next_.gi_running:

pass

next_.send(ip)

queue.task_done()

Thread(target=_run_target).start()

try:

while 1:

data = yield

queue.put(data)

except GeneratorExit:

queue.put(GeneratorExit)

@coroutine

def reduce_threaded(on_done):

m = {}

queue = Queue()

def _run_target():

nonlocal queue, m, on_done

while 1:

data = queue.get()

if data is GeneratorExit:

on_done(m)

return

else:

if data not in m:

m[data] = 1

else:

m[data] += 1

Thread(target=_run_target).start()

try:

while 1:

data = yield

queue.put(data)

except GeneratorExit:

queue.put(GeneratorExit)

And run it as follows

result = {}

def on_done(r):

global result

result = r

reducer = reduce_threaded(on_done)

flow = broadcast_threaded([

map_threaded('83.149.9.216', reducer),

map_threaded('93.114.45.13', reducer),

map_threaded('207.241.237.101', reducer),

])

# this is the source data

# We have 10000 lines in this log

%time

with open('assets/files/access.log', 'r') as fp:

for line in fp.readlines():

flow.send(line)

flow.close()

print(result) # result?

Then

CPU times: user 2 µs, sys: 0 ns, total: 2 µs

Wall time: 5.72 µs

{}

Oh, Why is the result empty?

Notice

-

When we use coroutine, we should consider whether coroutine may be overloaded. That is, at one point, can that coroutine both be pushed in and processed the data inside it? It is a rather dangerous case, causing the program to crash.

-

Avoid DAG designs

-

Only call

send()in synchronize, I mean only callsend()in the single thread

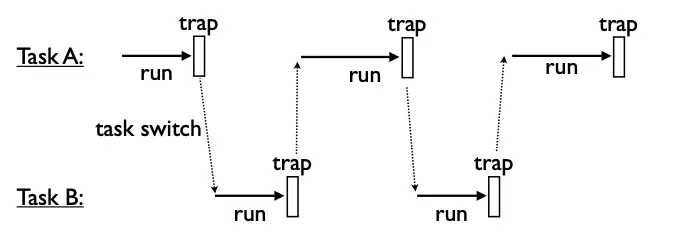

3. Scheduler for OS

Operation system scheduler

When a statement in a task hit trap, the task returns control to the OS and the OS executes the command or transfers control to another task in the queue.

It is a non-preemptive scheduler, and through the example below, you can understand the relationship between "trap" in the operating system and "yield" in Python.

from queue import Queue

class SystemCall:

__slots__ = ('sched', 'target')

def handle(self):

pass

class Task:

__slots__ = ('id', 'target', 'sendval')

_id = 0

def __init__(self, target):

Task._id += 1

self.id = Task._id

self.target = target

self.sendval = None

def run(self):

return self.target.send(self.sendval)

class Scheduler:

__slots__ = ('taskmap', 'ready')

def __init__(self):

self.taskmap = {}

self.ready = Queue()

def new(self, target):

task = Task(target)

self.taskmap[task.id] = task

self.schedule(task)

return task.id

def mainloop(self):

while self.taskmap:

task = self.ready.get()

try:

result = task.run()

if isinstance(result, SystemCall):

result.task = task

result.sched = self

result.handle()

continue

except StopIteration:

self.exit(task)

else:

self.schedule(task)

def schedule(self, task):

self.ready.put(task)

def exit(self, task):

print('Task %d terminated' % task.id)

del self.taskmap[task.id]

class GetTid(SystemCall):

def handle(self):

self.task.sendval = self.task.id

self.sched.schedule(self.task)

class NewTask(SystemCall):

def __init__(self, target):

self.target = target

def handle(self):

tid = self.sched.new(self.target)

self.task.sendval = tid

self.sched.schedule(self.task)

class KillTask(SystemCall):

def __init__(self, tid):

self.tid = tid

def handle(self):

task = self.sched.taskmap.get(self.tid, None)

if task:

task.target.close()

self.task.sendval = True

else:

self.task.sendval = False

self.sched.schedule(self.task)

OK, let's start server

def foo():

tid = yield GetTid()

print(f'I\'m foo and I am living in {tid} process')

for i in range(5):

print(f"Foo {tid} is in {i} step")

yield

def bar():

tid = yield GetTid()

print(f"I'm bar and I'm living in {tid} process")

yield NewTask(foo())

for i in range(3):

print(f"Bar {tid} is in {i} step")

yield

yield KillTask(1)

if __name__ == '__main':

sched = Scheduler()

sched.new(foo())

sched.new(bar())

sched.mainloop()

And you can see

I'm foo and I am living in 1 process

Foo 1 is in 0 step

I'm bar and I'm living in 2 process

Foo 1 is in 1 step

Bar 2 is in 0 step

Foo 1 is in 2 step

I'm foo and I am living in 3 process

Foo 3 is in 0 step

Bar 2 is in 1 step

Foo 1 is in 3 step

Foo 3 is in 1 step

Bar 2 is in 2 step

Foo 1 is in 4 step

Foo 3 is in 2 step

Task 1 terminated

Foo 3 is in 3 step

Task 2 terminated

Foo 3 is in 4 step

Task 3 terminated

It's magical.